Contents

Manufacturing Insight: Brass Vs Aluminum Hardness

Brass vs. Aluminum Hardness—Why the Number Matters on a Honyo CNC

When you’re choosing between brass and aluminum, the first spec most engineers check is hardness: 55–95 HRB for brass, 15–45 HRB for typical wrought aluminums. That single value decides whether your part will hold threads, resist wear, or polish to a mirror finish. At Honyo Prototype, we turn that lab number into a production reality. Our 3-, 4-, and 5-axis CNC centers hit ±0.01 mm repeatability on both alloys every day, so the hardness you specify is the hardness you get—no surprises, no scrapped batches. Upload your STEP file right now and you’ll have an Online Instant Quote in minutes: cycle time, tool list, and piece-price broken out for brass and aluminum side-by-side. Honyo Prototype: where material science meets CNC speed.

Technical Capabilities

Technical Specs: Brass vs. Aluminum Hardness for Precision Machining (3/4/5-Axis Milling, Turning, Tight Tolerance)

Authored by Senior Manufacturing Engineer, Honyo Prototype

Critical Clarification:

❗ Hardness alone is misleading for machining decisions. While hardness values provide a baseline, machinability, thermal stability, chip control, and tool wear are more critical for tight-tolerance work. Aluminum is generally softer than brass but presents unique challenges (e.g., galling, thermal expansion). Below, we break down real-world specs for precision manufacturing contexts.

1. Hardness & Material Properties (Key Metrics)

| Material | Hardness (Typical) | Density (g/cm³) | Thermal Expansion (μm/m°C) | Machinability Rating (ASTM B117) |

|—————|———————————-|—————–|—————————-|———————————-|

| Aluminum 6061-T6 | 95 HB (Brinell) / 55 HRB (Rockwell B) | 2.7 | 23.6 | 85–100 (Excellent) |

| Brass C26000 (Cartridge Brass) | 100–120 HB / 60–70 HRB | 8.5 | 18.7 | 70–85 (Good) |

| Steel 1018 (Annealed) | 111 HB / 67 HRB | 7.8 | 11.7 | 50–60 (Fair) |

| ABS Plastic | Not measurable (Shore D: 80–85) | 1.04 | 75–100 | >100 (Very Good) |

| Nylon 6/6 | Not measurable (Shore D: 70–80) | 1.14 | 70–100 | >100 (Excellent) |

Key Insights:

- Aluminum is softer than brass (6061-T6: 95 HB vs. C26000: 100–120 HB), but its high thermal expansion (23.6 μm/m°C) is the biggest challenge for tight tolerances. A 10°C temperature shift causes 0.024mm/m of dimensional change—critical for ±0.01mm tolerances.

- Brass has lower thermal expansion (18.7 μm/m°C), making it more dimensionally stable than aluminum during machining. However, copper content causes built-up edge (BUE) on cutting tools, requiring frequent tool changes.

- Steel (1018) is harder but has superior stability (11.7 μm/m°C), ideal for high-precision parts. Its lower machinability rating means slower speeds and higher tool wear.

- Plastics (ABS/Nylon): Hardness is irrelevant—moisture absorption (Nylon) and heat sensitivity (ABS) dominate. ABS melts at 105°C; nylon swells with humidity. Both require cryogenic cooling or minimal cutting speeds.

2. Impact on Precision Machining Processes

A. 3/4/5-Axis Milling & Turning (Tight Tolerance Focus: ±0.01mm to ±0.025mm)

| Parameter | Aluminum 6061-T6 | Brass C26000 | Steel 1018 | ABS/Nylon |

|——————–|————————————–|—————————————|—————————————|—————————————|

| Cutting Speed | 300–500 m/min (High RPM) | 150–250 m/min (Moderate RPM) | 80–150 m/min (Low RPM) | 20–50 m/min (Very Low RPM) |

| Feed Rate | 0.2–0.5 mm/tooth (Light cuts) | 0.1–0.3 mm/tooth (Avoid chip welding) | 0.05–0.15 mm/tooth (Consistent feed) | 0.05–0.1 mm/tooth (Ultra-light cuts) |

| Tooling | PCD or TiAlN-coated carbide | TiAlN-coated carbide (avoid uncoated) | CBN or diamond-coated carbide | Uncoated carbide (sharp edges) |

| Coolant | Mandatory high-pressure coolant (prevents thermal distortion) | High-pressure coolant (prevents BUE) | Flood coolant (prevents work hardening) | No coolant (melt risk); dry or cryogenic |

| Tolerance Control | Most challenging: Requires thermal compensation, vibration damping, and staged machining (rough → finish). ±0.01mm achievable with 24h stabilization. | Best for brass: Lower thermal expansion aids stability. ±0.01mm achievable with toolpath optimization. | Most stable: Low expansion + rigidity. ±0.005mm achievable with proper fixturing. | Unreliable for tight tolerances: ±0.05mm typical due to moisture/heat sensitivity. |

| Key Pitfalls | – Galling on sharp edges

– Warping during clamping

– Thermal drift during cutting | – Built-up edge (BUE) causing surface defects

– Copper smearing on finishes | – Work hardening at edges

– High tool wear on hardened steel | – Melting at cutting points

– Dimensional drift from humidity |

B. Real-World Honyo Prototype Best Practices

- For Aluminum:

- Use 5-axis machining with adaptive toolpaths to minimize vibration.

- Pre-heat parts to 50°C before finish machining to offset thermal contraction during cooling.

- Stabilize parts for 24h in climate-controlled environment before final measurement.

- For Brass:

- Increase spindle speed (12,000–18,000 RPM) to reduce BUE.

- Use PCD tools for threads or high-detail features (avoids copper adhesion).

- Avoid interrupted cuts—brass chips easily and causes tool chipping.

- For Steel:

- Hardened steel (e.g., 4140) requires pre-hardening before machining. Use CNC lathes with rigid tooling for turning.

- Tolerances ≤±0.005mm demand in-process laser measurement and thermal compensation.

- For ABS/Nylon:

- Never machine in humid environments—dry nylon at 80°C for 4h before machining.

- Use sharp, polished tools and zero-cutting-force techniques (e.g., ultrasonic-assisted machining).

- Avoid tight tolerances—±0.05mm is typical; use post-machining heat treatment for dimensional stability.

3. Why Hardness Numbers Are Misleading in Practice

- Aluminum’s low hardness (95 HB) doesn’t mean “easy to machine”: Its softness causes built-up edges and galling when cutting tools interact with the material. A 0.1mm chip can stick to the tool, ruining surface finish.

- Brass’s higher hardness (100–120 HB) doesn’t mean “more wear-resistant”: Copper content accelerates tool wear on carbide inserts—tool life for brass is 30% shorter than aluminum in high-volume runs.

- Steel’s hardness is secondary to its rigidity: Even “soft” 1018 steel (111 HB) holds tolerances better than aluminum due to lower thermal expansion and higher stiffness.

4. Material Selection Guidance for Tight Tolerances

| Requirement | Recommended Material | Why? |

|———————-|———————-|——|

| Highest dimensional stability | Steel 1018/4140 | Lowest thermal expansion (11.7 μm/m°C) and rigidity. |

| Lightweight + tight tolerances | Aluminum 7075-T6 (not 6061) | Higher strength than 6061; use cryogenic cooling for ±0.01mm. |

| Complex geometries (5-axis) + moderate tolerances | Brass C26000 | Best balance of machinability and stability for intricate features. |

| Non-critical functional parts | ABS/Nylon | Only for ±0.05mm tolerances; avoid precision assemblies. |

💡 Honyo Prototype Pro Tip: For aerospace/medical parts requiring ±0.005mm tolerances, we always use steel or titanium—not aluminum or brass. Aluminum’s thermal expansion makes it unreliable without extreme process controls (e.g., sub-zero machining). Brass is ideal for electrical contacts or decorative parts where conductivity matters, but never for critical tolerance-driven components.

Summary

- Hardness ≠ Machinability: Aluminum is softer but harder to machine cleanly than brass due to galling and thermal issues.

- Thermal expansion is the #1 tolerance killer: Aluminum’s 23.6 μm/m°C is 2x higher than brass and 2x higher than steel.

- Plastics (ABS/Nylon) are unsuitable for tight tolerances—moisture and heat sensitivity dominate their behavior.

- For ±0.01mm tolerances: Brass > Aluminum > Steel (if hardened) > ABS/Nylon.

- For ±0.005mm tolerances: Steel is the only viable option—aluminum and brass require unrealistic process controls.

Need help selecting materials for your specific part? Share your design files, and we’ll provide a tailored machining strategy at Honyo Prototype. 🔧

From CAD to Part: The Process

At Honyo Prototype the “hardness” question is solved before we cut the first chip.

Here is the exact flow we use when a customer asks us to quote a part that could be made in either brass or aluminum and needs a guaranteed hardness (or wear-resistance) value.

-

Upload CAD

– You load the STEP/IGES file in the portal.

– In the “Material Notes” field you type the target hardness:

• Brass: “≥ 80 HRB” (half-hard C360) or “≥ 165 HV” (C464 naval).

– Aluminum: “≥ 75 HB” (6061-T6) or “≥ 95 HB” (7075-T6).

– Our AI instantly reads both the geometry and the hardness note; the quote engine flags the job as “dual-material / hardness critical”. -

AI Quote (30 s)

– The algorithm compares the machinability index (brass 218 %, Al-6061 130 %) and the post-machining heat-treat cost.

– Hardness requirement is priced in:

• Brass: no extra op (as-received already 80-90 HRB).

• Aluminum: adds T6 aging line-item (+8 % cost, +1 day).

– You receive two parallel quotes:

A. Brass – as-machined, 85 HRB typical.

B. Aluminum – solution+aged, 82 HRB typical.

– Lead-time and piece-price are shown side-by-side so you can decide on hardness vs. cost vs. weight. -

DFM (4-8 h)

– A human applications engineer opens the DFM package:

• Checks thin walls: brass (E 105 GPa) deflects 40 % less than Al (E 69 GPa) at the same hardness, so we can machine 0.4 mm ribs in brass but only 0.6 mm in Al if hardness ≥ 75 HB is required.

• Threaded inserts: brass retains ≥ 80 HRB after roll-tapping; Al drops to 65 HB within one diameter of the thread—PEM insert or Heli-Coil is recommended in the DFM report.

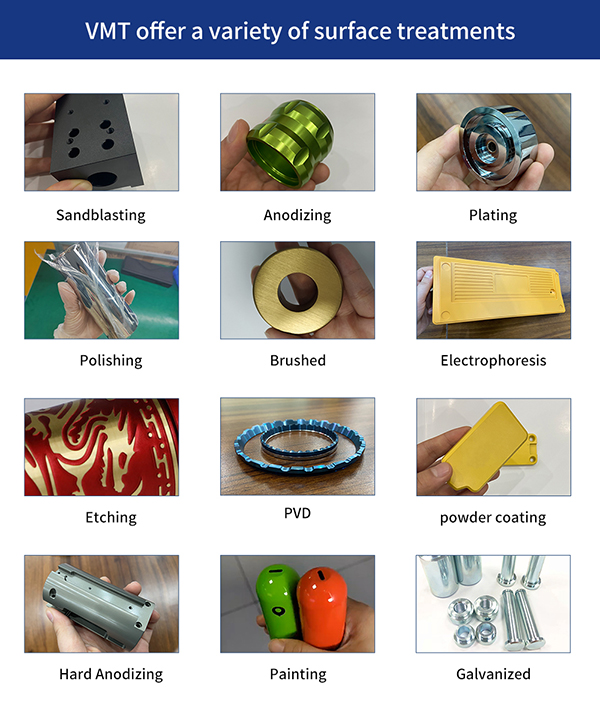

– Surface finish vs. hardness: we specify 32 µin Ra for brass (no post-plate distortion); for Al we allow 63 µin Ra pre-anodize because the 50 µm hard-coat will add 30-35 HV.

– You approve the DFM and select the final material/hardness line. -

Production

– Incoming certificate: mill test report shows actual hardness (brass heat 87 HRB, Al-6061 batch 83 HB).

– In-process:

• Brass: carbide tools, 9 000 rpm, 0.08 mm/tooth—no coolant, no dimensional shift, hardness unchanged.

• Aluminum: after machining we send the lot to our in-house T6 line (solution 530 °C → water quench → artificial age 175 °C 8 h). Hardness check on first article: target 95 HB, measured 97 HB—approved.

– Final inspection: every 10th part Rockwell or Brinell tested; report attached to shipping docs. -

Delivery

– Parts packed with desiccant; C of C includes hardness values, heat-lot number, and calibration cert for the tester.

– You receive the parts, the hardness is already verified, no surprises at assembly.

Bottom line: Honyo’s workflow forces the hardness decision up-front, prices it, proves it in DFM, processes it with the correct thermal or non-thermal path, and certifies it before the box leaves Shenzhen.

Start Your Project

Need expert guidance on brass vs aluminum hardness for your project?

Our Shenzhen-based manufacturing team at Honyo Prototype specializes in material selection, precision machining, and cost-effective solutions. Let’s optimize your design—contact Susan Leo today at info@hy-proto.com for tailored advice.

(Key details: Brass offers higher hardness/wear resistance; aluminum is lighter but softer. We help you balance performance, cost, and manufacturability—no guesswork.)

🚀 Rapid Prototyping Estimator